My shout to the world

Tuesday, 22 October 2024

The real story of Benghazi

A CIA insider’s account of what happened on 9/11/12

https://www.politico.eu/article/the-real-story-of-benghazi/

MAY 12, 2015 8:40 PM CET

BY MICHAEL MORELL

On September 11, 2012, I was in Amman, Jordan, part of my routine international visits as deputy director of the CIA. I had already been to Israel and was due the next day to depart for Saudi Arabia. I had dined that night with the head of the Jordanian military and the head of Jordanian intelligence, and upon returning to the hotel I checked in with Washington and caught up on e-mail before going to bed. Earlier in the day I had seen reports about an incident in Cairo that, although troubling, seemed to have ended without too much damage and with no injuries.

It wasn’t long before I was woken from a sound sleep by a knock on the door from one of my assistants, who told me that another incident had taken place, this one at the State Department facility in Benghazi, and that CIA security officers had responded in order to assist. My assistant told me that one State Department officer had been killed and the ambassador’s whereabouts were unknown. She said that everyone else had relocated to the CIA base in Benghazi and was believed safe, adding that our chief of station (COS) in Tripoli was sending security officers as reinforcements from Tripoli to Benghazi.

Then, early the next morning, my assistant banged on my door again to tell me that the CIA base was now under heavy attack. I threw on some sweats and made my way to my command post, just down the hall from my room.

The city of Benghazi was vitally important in Libya. It had been the center of much of the opposition to Muammar Qadhafi for years, and it remained a key outpost used by the United States to understand developments during the revolution and to influence key players in eastern Libya after Qadhafi. CIA had established a presence in Benghazi with the mission of collecting intelligence—contrary to some press reporting, it did not play any role in moving weapons from Libya to the opposition in Syria and neither did any other CIA officer or facility in Libya.

Normally I would not be able to confirm the existence of a CIA base overseas, let alone describe its mission. But because of the tragic events in Benghazi on September 11, 2012—and the controversial aftermath—the Agency’s role there has since become declassified, which allows me to discuss it here.

The CIA mission in Benghazi is worth discussing because it’s important to explain what happened—and what didn’t happen—in Benghazi on that fateful day.

Muammar Qadhafi’s departure from the scene in Libya in 2011 was a good thing in that it prevented the slaughter of thousands of his own citizens. But what followed was a failed state that provided room for extremist groups to flourish. At the end of the day, are the Libyan people better off after their revolution than before? I’m not so sure. Certainly what occurred in Libya was a boon to al Qaeda all across North Africa and deep in the Sahel, which includes parts of Mauritania, Mali, and Niger. The fledgling government that replaced Qadhafi’s lacked even a rudimentary ability to govern and militias with various ideologies reigned in large parts of the country.

Because of this lack of governance, during the spring and summer of 2012, the security situation across Libya, deteriorated. CIA analysts accurately captured this situation, writing scores of intelligence pieces describing in detail how the situation in Libya was becoming more and more dangerous. One of them from July was titled Libya: Al Qaeda Establishing Sanctuary. These pieces were shared broadly across the executive branch and with the members and staff of the intelligence committees in Congress.

With the anniversary of 9/11 on the horizon and the security situation throughout much of the Arab world in flux, in early September 2012 the CIA had sent out to all its stations and bases worldwide a cable warning about possible attacks. There was not any particular intelligence regarding planned attacks; we routinely sent such cables each year on the anniversary of 9/11—but we did want our people and their US government colleagues to be extra vigilant.

We had also sent an additional cable to Cairo because we had picked up specific intelligence from social media that there might be a violent demonstration there in reaction to an obscure film made in the United States that many Muslims believed insulted the Prophet Muhammad. The social media posting encouraged demonstrators to storm our embassy and kill Americans. It turned out that our embassy in Cairo had independently picked up the same social media report and had already taken precautions. The ambassador and most of her staff were not at the Cairo embassy on 9/11/12 when a mob breached the walls of the compound, setting fires, taking down American flags, and hoisting black Islamic banners. News of what the protesters had accomplished in Cairo spread quickly through Arab media, including to Benghazi.

The State Department facility in Benghazi has been widely mischaracterized as a US consulate. In fact it was a Temporary Mission Facility (TMF), a presence that was not continuously staffed by senior personnel and that was never given formal diplomatic status by the Libyan government. The CIA base—because it was physically separate from the TMF—was simply called “the Annex.”

In the months leading up to the September 11 attacks, many assaults and incidents directed at US and other allied facilities occurred in Benghazi—roughly twenty at the TMF alone—and CIA analysts reported on every significant one, including an improvised explosive device (IED) that was thrown over the wall of the TMF, an attack on the convoy of the UN special envoy to Libya, and an assassination attempt against the British ambassador to Libya.

As a result of the deterioration in security in Libya, we at CIA at least twice reevaluated our security posture in Benghazi and made significant enhancements at the Annex. It was only later—after the tragedy of 9/11/12—that we learned that only a few security enhancements had been made at the TMF. CIA does not provide physical security for State Department operations. Why so few improvements were made at the TMF, why so few State Department security officers were protecting the US ambassador, Chris Stevens, why they allowed him to travel there on the anniversary of 9/11, and why they allowed him to spend the night in Benghazi are unclear. I would like to know the conversations that took place between Stevens and his security team when the ambassador decided to go visit Benghazi on 9/11/12. These were all critical errors. When I traveled to Libya, my security detail would not even allow me to spend the night in Tripoli, and the leader of my security team brought what seemed to me like a small army to Libya to protect me.

Now our personnel in Benghazi were under attack.

When I made it to the command post that morning, there was a security tent that covered two tables holding secure phone lines and computers capable of accessing CIA’s top secret network.

At CIA we make use of an instant messaging program called Sametime for informal quick communications among our personnel worldwide. I “sametimed” the Agency’s chief of station in Tripoli to ask him for an update and to see if I could help him in any way.

During our back-and-forth messaging over Sametime, the chief recounted what he knew about the attack on the Annex, which had by that time just concluded. He told me two officers had been killed in a mortar attack on the Annex—I simply typed, “I am sorry”—bringing the total number of Americans killed to four, including Ambassador Stevens, who had been reported dead at a Benghazi hospital. Stevens was a legend in the diplomatic corps for his understanding of Arab culture and for his ability to work effectively in it. The others were Sean Smith, a State Department communications officer, killed at the TMF, and Glen Doherty and Tyrone Woods, two security officers, both killed at the Annex.

Over our nearly two-hour on-again, off-again instant messaging conversation, the COS said that he had decided to pull his people out of Benghazi and was working on getting transportation for them and the State Department personnel back to Tripoli. I asked him several times if he needed anything, if I could help in any way. He said he thought he had everything he needed at the moment. I told him that I wanted “to know when everyone is safe,” adding that I was heading to the embassy in Amman and that he could reach me there. I signed off by typing, “Hang in there. I am praying for you.” When I stepped away from the computer, I told my staff that I was very impressed with how the COS was handling a very difficult situation and that I was proud of him. He was calm and determined—and was making all the right decisions.

From the embassy in Jordan, I called CIA Director David Petraeus and told him that I thought I should cut my trip short. He agreed. I hung up the phone and told my staff, “We are going home.”

There are a number of myths about what happened during the nighttime and early-morning hours of the Benghazi attacks. One misconception is that there was a single four-hour-long battle. Another myth is that the attacks were well-organized, planned weeks or even months in advance. In fact, there were three separate attacks that night, none of them showing evidence of significant planning, but each of them carried out by Islamic extremists, some with connections to al Qaeda, and each attack more potent than the one before. Since the definition of terrorism is violence perpetrated against persons or property for political purposes, each attack in Benghazi was most definitely an act of terrorism—no matter the affiliation of the perpetrators, no matter the degree of planning, and no matter whether the attack on the TMF was preceded by a protest or not (an issue that would take on enormous political importance in the weeks and months ahead).

The first attack was on the State Department’s Temporary Mission Facility. We know from having monitored social media and other communications in advance that the demonstration and violence in Cairo were sparked by people upset over a YouTube video that portrayed the Prophet Muhammad negatively. We believe that in Benghazi—over six hundred miles away—extremists heard about the successful assault on our embassy in Egypt and decided to make some trouble of their own, although we still do not know their motivations with certainty. Most likely they were inspired by the prospect of doing in Benghazi what their “brothers” had done in Cairo.

Some may have been inspired by a call Ayman al-Zawahiri— the leader of al Qaeda in Pakistan—had made just the day before for Libyans to take revenge for the death of a senior al Qaeda leader of Libyan origin in Pakistan. Still others might have been motivated by the video—although I should note that our analysts never said the video was a factor in the Benghazi attacks. Abu Khattala, a terrorist leader and possibly one of the ring leaders of the attacks, said that he was in fact motivated by the video. Khattala is now in US custody and under indictment for the role he played in the assault.

I believe that, with little or no advance planning, extremists in Benghazi made some phone calls, gathering a group of like-minded individuals to go to the TMF. When they attacked, at about 9:40 p.m. local time, the assault was not well organized—they seemed to be more of a mob who intended to breach the compound and see what damage they could do.

When you assess the information from the video feed from the cameras at the TMF and the Annex, there are few signs of a well-thought-out plan, few signs of command and control, few signs of organization, few signs of coordination, few signs of even the most basic military tactics in the attack on the TMF. Some of the attackers were armed with small arms; many were not armed at all. No heavy weapons were seen on the videotape. Many of the attackers, after entering through the front gate, ran past buildings to the other end of the compound, behaving as if they were thrilled just to have overrun the compound. They did not appear to be looking for Americans to harm. They appeared intent on looting and conducting vandalism. When they did enter buildings, they quickly exited with stolen items. One young man carried an Xbox, another had a suit bag stolen from an American’s quarters. The rioters started to set fires, but there was no indication that they were targeting anyone. They entered one building with Americans hiding inside, did not find them, and quickly departed. Through it all, none of the Department of State security officers at the TMF fired a weapon.

Clearly, this was a mob looting and vandalizing the place—with tragic results. It was a mob, however, made up of a range of individuals, some of whom were hardened Islamic extremists. And it was a mob that killed two Americans by setting fires to several buildings. After reviewing the information in the video, I was in favor of releasing it publicly. Doing so would have helped Americans better understand the nature of the attack. I do not know why the White House did not release the information—this despite urgings to do so from Jim Clapper, the director of national intelligence, and from other senior intelligence officials, including me. The videos, at this writing, still have not been declassified.

The ambassador and Sean Smith were in the main building when a fire was set there, and the thick black smoke that quickly enveloped the building suffocated them. There is no evidence that the attackers were targeting the ambassador specifically or US officials generally when they set that fire or any of the other fires that night.

About an hour after the mob stormed the compound, officers from the CIA base came to the aid of their State Department colleagues. The Agency security team fired the first American shots of the night, exchanging gunfire with the attackers, pushing them back, and then helping the State Department security officers search (unsuccessfully) for the ambassador. They recovered the body of Sean Smith, and unable to find the ambassador, organized a retreat to the Annex.

The second attack of the evening was on the CIA base. This attack occurred just after midnight and within minutes of the CIA team’s arrival back from the TMF. My assessment is that some of those who had conducted the assault on the TMF—the best armed and most highly motivated of the group—followed the State Department officers back to the Annex after they ran the roadblock. The attackers on the Annex were armed with light weapons and rocket-propelled grenades and CIA and State Department security officers drove them off in what was a short firefight. But, unlike at the TMF, this was a more organized attack with the clear goal of killing Americans.

Three and a half hours after the start of the assault on the TMF, reinforcements arrived in Benghazi in the form of CIA and military personnel who had managed to charter an aircraft from Tripoli and fly to Benghazi to assist their colleagues. After being delayed at the airport in Benghazi for some time, they arrived at the Annex at 5 a.m. Some of them took up fighting positions on the roof of the main building on the Agency base. They arrived with virtually no time to spare, as the third attack of the night was about to begin. There is no evidence that the final group of attackers followed our officers from the airport to the Annex, as has been alleged in the press.

It was at approximately five fifteen a.m. that the third, final, and most sophisticated attack of the night occurred. My subsequent analysis is that after the extremists were driven from the CIA Annex the first time, they regrouped, acquiring even heavier weapons and most likely additional fighters. Most important, they returned with mortars. Five mortar rounds were fired and three made direct hits on the roof of the main building, killing Glen Doherty and Tyrone Woods and seriously injuring others.

Long after the attack, I asked myself, “Why did the attackers use only five mortar rounds?” They had time and space to fire additional rounds as they had driven our security officers from their positions.

This piece is adapted from Michael Morell’s new book, written with Bill Harlow, The Great War of Our Time: The CIA’s Fight Against Terrorism—From al Qa’ida to ISIS

The logical answer to me is clear—they had only five mortars. If this had been an assault with days, weeks, or months of planning, the terrorists would have been much better armed and they would have brought those weapons to the first assault at the TMF as well as the first assault on the CIA base. And they would have had more than just five mortar rounds for the second assault on the Annex. Libya, after all, is a country awash in weapons, including mortars. Instead all three were opportunistic attacks that escalated in sophistication during the night as the extremists had more time to organize.

As awful as it was, the events of the evening could have been much worse without the incredible heroism of a handful of CIA officers and military personnel.

Had CIA officers not responded to the TMF, there undoubtedly would have been more fatalities there. During the fight at the CIA base, the actions of two Special Forces officers stood out. In Tripoli, when the first attacks began, they responded as you would expect our country’s most elite soldiers to respond. They volunteered to go to Benghazi and stand shoulder to shoulder with our officers in a firefight with terrorists. While they were not technically in the chain of command, their training and experience, their excellent judgment, and their calm demeanor under fire effectively resulted in their taking charge at the Annex. Everyone looked to them for leadership, and they provided it. And they were the ones who recovered the dead and wounded officers from the rooftop immediately after the mortar attack.

One of our injured officers on the roof where Glen Doherty and Tyrone Woods were killed was nearly unconscious and unable to move. Fearing that the mortar fire could resume at any moment, the two Special Forces operatives improvised a maneuver in which one of them strapped the six-foot-three, 240-pound man to the other’s back. In a supreme test of strength, focus, and determination, the soldier bearing our wounded officer scaled a wall at the edge of the roof and then worked his way down a rickety ladder—all under the constant threat of enemy fire. Both Special Forces officers received awards for their bravery and heroic actions in response to the tragedy in Benghazi.

Friday, 7 July 2023

Coast watchers

Australia's Secret Army: The story of the Coast Watchers, the unsung heroes of Australia’s armed forces during World War II is published by Hatchette Australia

Saturday, 1 July 2023

Sunday, 6 March 2022

How to Read the Sky at Night : Southern Cross

How to Read the Sky at Night

Practical Astronomy for Date, Time, and Direction Finding

This new page describes some practical astronomy that you can learn quickly — for finding direction, and other things that people could read from the sky in ancient times, before modern technology.

The information on this page at first will relate only to the southern hemisphere, later I might add some northern hemisphere information. There are already a lot of websites about the north hemisphere.

On This Page

The Basics

The Celestial Sphere

Finding the Time and the Date by the Stars

Finding Direction from the Stars

Why Learn Observational Astronomy?

With regards to the subject matter of survival.ark.net.au, there are at least three reasons:

You'll gain practical skills that people used in ancient times, such as how to find time and direction.

Watching the night sky can help a lot to get your mind into more of a peaceful state that's closer to that of ancient people. This somewhat meditative state comes from the slowing down of your thoughts that will happen if you look at the sky enough, and also from using more of your peripheral vision.

These things in the sky can become quite interesting once you start to learn about them them. They are also one of the few things in our lives that's not affected by any of the problems we have in the modern world. No matter what happens to Planet Earth, everything in the distant world of the stars will remain just like it always has. This can become a source of stability and peace.

The Basics

Most people already know that the Sun rises in approximately the east, and sets in (approximately) the west. A good first practical exercise for this is to start to take some notice of where the Sun is throughout the day. Where in the sky is the Sun right now?

If it's night-time right now you might say that the Sun isn't in the sky at all. But it's still somewhere. See if you can point your arm towards where the Sun would be right now, daytime or night-time.

The second thing to know is that everything else "natural" in space, that you can see in the sky (excluding man made objects like satellites and/or any visiting aliens) also moves pretty much in the same fashion as the Sun. That is the Moon, the planets, and most of the stars all approximately rise in the east and set in the west.

The Celestial Sphere

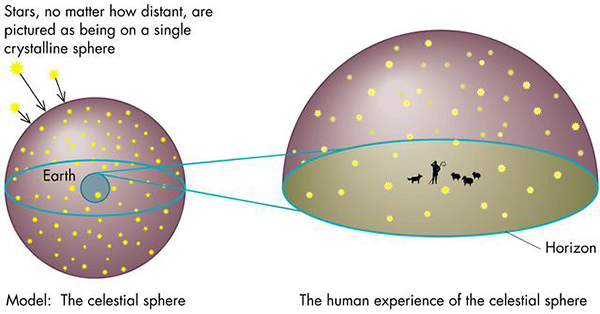

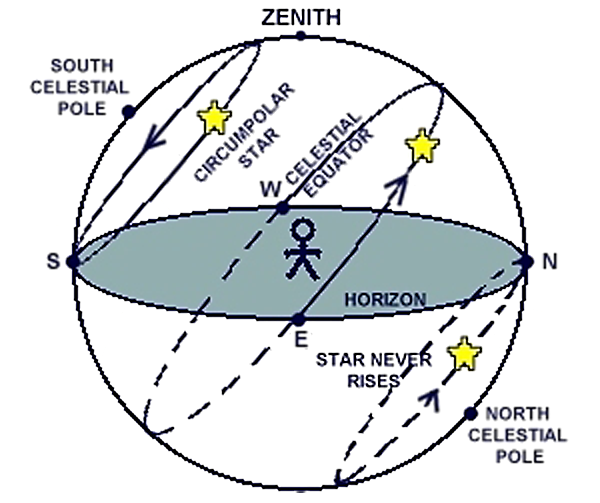

A more accurate way to describe how these sky objects move is to imagine the Earth (and you on the Earth) at the centre of a huge invisible sphere, which makes up the sky. This sphere rotates on the same axis as the Earth does, that is from the North Pole of the Earth to the South Pole.

Imagine that all the stars are stuck to this sphere, and rotate with it around the sky.

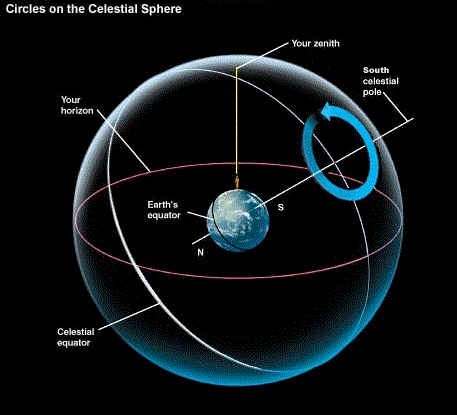

The celestial sphere (and the stars "on" it) rotate around the north and south poles of the sky, called the north and south celestial poles. Unless you are right on the equator you can only ever see one of these poles, and the other one is below the horizon. In the Southern Hemisphere we can see the southern celestial pole.

The horizon is the red line in the diagram below, representing the ground. You can see everything above the red line, and everything below it is below the horizon and invisible.

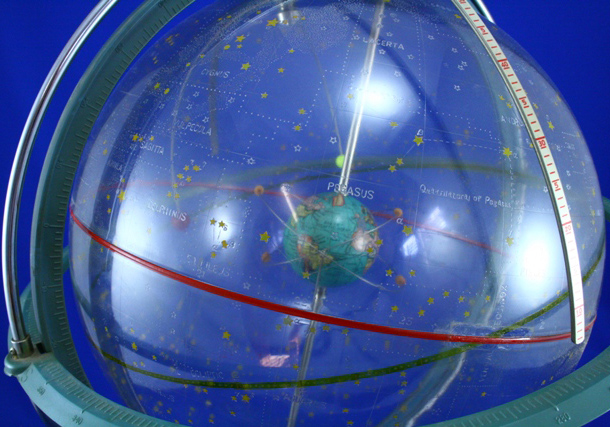

Apart from tiny movements that you need large telescopes to measure, the positions of all the stars as we see them relative to each other, are fixed on this sphere. You can imagine they are glued on, or painted on like in the plastic celestial sphere model shown below. Only the very distant objects, like the stars, are fixed onto the sphere. This includes all the stars (apart from the Sun), plus other objects from astronomy including galaxies, star clusters, nebulae, and the "milky way". Closer objects (within our own solar system) including the Sun, Moon, planets and comets will move relative to this sphere of fixed stars.

The height of the celestial pole above the horizon (assuming a flat horizon with no hills or buildings etc in the way) will be equal to your latitude. For Sydney this is about 35 degrees. Therefore in Sydney the celestial pole will be about 35 degrees above the horizon — or a bit over 1/3 of the distance from the ground up to the highest point in the sky (i.e. straight up, which is called the zenith, and is 90 degrees above the horizon).

The stars close to the pole will be seen to move clockwise (anticlockwise in the northern hemisphere) in a circle around the pole, and they will be visible all year around, and at any time of the night (as long as there are no clouds in the way). By "close to the pole", specifically this means closer to the pole than your latitude, measured in degrees.

Taking a long exposure time photo of the stars shows how the sky appears to rotate around the celestial pole in the middle.

Photo: Bendigo amateur photographer Lincoln Harrison.

From a latitude close to the equator, the celestial pole appears close to the ground as in the photo below from Mount Kilimanjaro.

Photo: dailygalaxy.com.

Finding the Time and the Date by the Stars

The diagram below (from Sydney Observatory) shows how the southern cross moves around the celestial pole (in the centre of the circle) in one night. This is assuming that it starts at the top position about about 6pm, which will only happen around June.

The diagram is slightly wrong because in 12 hours (such as from 6pm to 6am), the cross should move almost exactly 180 degrees. It's actually very close to 180.5 degrees in 12 hours. This is because in one full day, the clock rotates almost exactly 361 degrees, i.e. one degree more than a full circle. Every day the starting position of the clock moves forward by one degree so that in a full year of 365 days, its gone around all the way around and back to where it was a year before.

This diagram (above) can be used to find the approximate time, providing you know what position the cross started from at the start of the night (e.g. at 6pm). The cross moves around this big circle like the hour hand of a massive 24-hour analogue clock which takes up about 1/3 of the entire visible sky. Note that the hour hand on a 24-hour clock moves half as fast as on an ordinary 12-hour clock, so that it takes a full 24 hours to go all the way around.

Reading time from the Southern Cross is like having the clock below stamped onto the sky, but only the hour hand — and with the clock body itself rotated to a position that depends on the date, so that at different dates there will be different starting times at the top of the dial. The diagram under the clock shows how the starting position of the cross (at 8:00 pm) changes over different months. The rotation of this clock body against the sky (and therefore starting position of the cross) happens very slowly, by about 4 minutes on the clock dial per day (which is 1/15th of an hour, or one degree — not very much) , so that it turns a full circle exactly once per year.

Finding the Date

The next diagram shows how the position of the Southern Cross varies on different dates. The Cross will be in these positions at approximately 8:00pm (this would be 9:00 pm daylight savings time in summer) in the months as labelled below. In any given night it will rotate clockwise, starting from this position at 8:00pm. As an exercise, see if you can find the Southern Cross in the sky tonight (or soon), and compare its position to the diagrams here. Note that these times are independant of what timezone you're in. This is because it's the relative position of the Sun compared to the background stars (on the celesital sphere) that matters, and this is the same anywhere on Earth at any given time of year.

You can use this diagram to find the approximate date, if you view the position of the Southern Cross when you know its about 8:00 pm — i.e. about 2 hours after sunset in midwinter, or shortly after sunset in midsummer (this is 9pm in daylight savings areas). If you had no access to modern technology whatsoever, this method would still work just as well as it does now to tell you, approximately, what month of the year it is.

If its another time than 8pm, you can calculate where the cross would be at 8pm by thinking of how much it would rotate either back or forwards based on how many hours away it is from 8pm. This all sounds complicated but once you get used to looking at the position of the cross often, it becomes second nature. It's easier than learning to tell the time (hours, minutes, and seconds) on an analogue clock.

Stars close to the north celestial pole will move in a circle around the north celestial pole, and will never be seen from the southern hemisphere. These are seen in the lower right corner of the picture below (labelled with "Star never rises").

Stars within the leftmost circle are always visible (like the Southern Cross from many southern latitudes) and are called "circumpolar". Stars in between these two circles (not really close to either pole) will rise and set at different times, depending on the time and date. The middle line is called the celestial equator and is the Earth's actual equator projected onto the sky. Stars right on the celestial equator will rise in exactly the east (provided you have a flat horizon) and set in exactly the west.

Finding Direction from the Stars

In the Southern Hemisphere, the easiest direction to learn to find from the night sky is south.

Finding South

The easiest way to find south is using the Southern Cross. The position of the cross will vary with the time and date (like in the pictures above with grey backgrounds), but it's long end will always point directly at the southern celestial pole.

There are three ways you can find the pole using the Southern Cross. You can use any one of these (or use two or three to be more accurate):

The southern celestial pole is about 5 times as far away from the cross as the distance from one end of the Southern Cross to the other.

If you draw a line in the direction the cross points, and another line at right angles to the line between the two "pointers", where these lines meet is the pole.

If you can find the bright star Achernar, the pole is halfway between Archenar and the cross.

Once you know where the pole is, south on the horizon is directly below the pole (like the head of the arrow below).

Image by Conger, Cristen. "How to Find True North", HowStuffWorks.com.

To Be Continued...

Coming Soon

Next I'll cover the positions of the Sun, and the seasons, and the position and phases of the Moon, and the months. Also some of the other stars, star maps/charts, the constellations, the planets, and comets.

Recommended Reading

Philip's Planisphere. This practical hour-by-hour tracker of the stars and constellations is an essential travel accessory for astronomy enthusiasts visiting Australia, New Zealand, South Africa or southern South America. Turn the oval panel to the required date and time to reveal the whole sky visible from your location.

Philip's Planisphere. This practical hour-by-hour tracker of the stars and constellations is an essential travel accessory for astronomy enthusiasts visiting Australia, New Zealand, South Africa or southern South America. Turn the oval panel to the required date and time to reveal the whole sky visible from your location. Invaluable for both beginners and advanced observers, Philip's Planisphere (Latitude 35 South) is an essential travel accessory for astronomy enthusiasts visiting Australia, New Zealand, South Africa or southern South America. To use this practical hour-by-hour tracker of the stars and constellations, you simply turn the oval panel to the required date and time to reveal the whole sky visible from your location.The map, by the well-known celestial cartographer Wil Tirion, shows stars down to magnitude 4, plus several deep-sky objects, such as the Pleiades, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds (LMC and SMC), and the Orion Nebula (M42). Because the planets move round the Sun, their positions in the sky are constantly changing and they cannot be marked permanently on the map; however, the back of the planisphere has tables giving the positions of Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn for every month until 2020.The planisphere is supplied in a full-colour wallet that contains illustrated step-by-step instructions for how to use the planisphere, how to locate planets, and how to work out the time of sunrise or sunset for any day of the year.

It explains all the details that can be seen on the map - the magnitudes of stars, the ecliptic and the celestial coordinates. In addition, the section 'Exploring the skies, season by season' introduces the novice astronomer to the principal celestial objects visible at different times of the year. Major constellations are used as signposts to navigate the night sky, locating hard-to-find stars and some fascinating deep-sky objects. The movement of the stars is also explained.

Tuesday, 30 November 2021

Saturday, 30 October 2021

What Happened: Dr. Jay Bhattacharya on 19 Months of COVID

Recorded on October 13, 2021 From the very beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya has been on the front lines of analyzing, studying, and even personally fighting the pandemic. In this wide-ranging interview, Dr. Bhattacharya takes us through how it started, how it spread throughout the world, the efficacy of lockdowns, the development and distribution of the vaccines, and the rise of the Delta variant. He delves into what we got right, what we got wrong, and what we got really wrong. Finally, Dr. Bhattacharya looks to the future and how we will learn to live with COVID rather than trying to extinguish it, and how we might be prepared to deal with another inevitable pandemic that we know will arrive at some point. For further information: https://www.hoover.org/publications/u... Interested in exclusive Uncommon Knowledge content? Check out Uncommon Knowledge on social media!

Tuesday, 5 October 2021

Vaccinating people who have had covid-19: why doesn’t natural immunity count in the US?

This article has a correction. Please see:

Vaccinating people who have had covid-19: why doesn’t natural immunity count in the US? - September 15, 2021

Jennifer Block, freelance journalistAuthor affiliations

writingblock@protonmail.com

Twitter: @writingblock

The US CDC estimates that SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 100 million Americans, and evidence is mounting that natural immunity is at least as protective as vaccination. Yet public health leadership says everyone needs the vaccine. Jennifer Blockinvestigates

When the vaccine rollout began in mid-December 2020, more than one quarter of Americans—91 million—had been infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate.1 As of this May, that proportion had risen to more than a third of the population, including 44% of adults aged 18-59 (table 1).

Table 1

Estimated total infections in the United States between February 2020 and May 2021*

View popup

View inline

The substantial number of infections, coupled with the increasing scientific evidence that natural immunity was durable, led some medical observers to ask why natural immunity didn’t seem to be factored into decisions about prioritising vaccination.234

“The CDC could say [to people who had recovered], very well grounded in excellent data, that you should wait 8 months,” Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease specialist at University of California San Francisco, told Medpage Today in January. She suggested authorities ask people to “please wait your turn.”4

Others, such as Icahn School of Medicine virologist and researcher Florian Krammer, argued for one dose in those who had recovered. “This would also spare individuals from unnecessary pain when getting the second dose and it would free up additional vaccine doses,” he told the New York Times.5

“Many of us were saying let’s use [the vaccine] to save lives, not to vaccinate people already immune,” says Marty Makary, a professor of health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University.

Still, the CDC instructed everyone, regardless of previous infection, to get fully vaccinated as soon as they were eligible: natural immunity “varies from person to person” and “experts do not yet know how long someone is protected,” the agency stated on its website in January.6 By June, a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 57% of those previously infected got vaccinated.7

As more US employers, local governments, and educational institutions issue vaccine mandates that make no exception for those who have had covid-19,8 questions remain about the science and ethics of treating this group of people as equally vulnerable to the virus—or as equally threatening to those vulnerable to covid-19—and to what extent politics has played a role.

The evidence

“Starting from back in November, we’ve had a lot of really important studies that showed us that memory B cells and memory T cells were forming in response to natural infection,” says Gandhi. Studies are also showing, she says, that these memory cells will respond by producing antibodies to the variants at hand.91011

Gandhi included a list of some 20 references on natural immunity to covid in a long Twitter thread supporting the durability of both vaccine and infection induced immunity.12 “I stopped adding papers to it in December because it was getting so long,” she tells The BMJ.

But the studies kept coming. A National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded study from La Jolla Institute for Immunology found “durable immune responses” in 95% of the 200 participants up to eight months after infection.13 One of the largest studies to date, published in Science in February 2021, found that although antibodies declined over 8 months, memory B cells increased over time, and the half life of memory CD8+ and CD4+ T cells suggests a steady presence.9

Real world data have also been supportive.14 Several studies (in Qatar,15 England,16 Israel,17 and the US18) have found infection rates at equally low levels among people who are fully vaccinated and those who have previously had covid-19. Cleveland Clinic surveyed its more than 50 000 employees to compare four groups based on history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination status.18 Not one of over 1300 unvaccinated employees who had been previously infected tested positive during the five months of the study. Researchers concluded that that cohort “are unlikely to benefit from covid-19 vaccination.” In Israel, researchers accessed a database of the entire population to compare the efficacy of vaccination with previous infection and found nearly identical numbers. “Our results question the need to vaccinate previously infected individuals,” they concluded.17

As covid cases surged in Israel this summer, the Ministry of Health reported the numbers by immunity status. Between 5 July and 3 August, just 1% of weekly new cases were in people who had previously had covid-19. Given that 6% of the population are previously infected and unvaccinated, “these numbers look very low,” says Dvir Aran, a biomedical data scientist at the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, who has been analysing Israeli data on vaccine effectiveness and provided weekly ministry reports to The BMJ. While Aran is cautious about drawing definitive conclusions, he acknowledged “the data suggest that the recovered have better protection than people who were vaccinated.”

But as the delta variant and rising case counts have the US on edge, renewed vaccination incentives and mandates apply regardless of infection history.8 To attend Harvard University or a Foo Fighters concert or enter indoor venues in San Francisco and New York City, you need proof of vaccination. The ire being directed at people who are unvaccinated is also indiscriminate—and emanating from America’s highest office. In a recent speech to federal intelligence employees who, along with all federal workers, will be required to get vaccinated or submit to regular testing, President Biden left no room for those questioning the public health necessity or personal benefit of vaccinating people who have had covid-19: “We have a pandemic because of the unvaccinated ... So, get vaccinated. If you haven’t, you’re not nearly as smart as I said you were.”

Staying firm

Other countries do give past infection some immunological currency. Israel recommends that people who have had covid-19 wait three months before getting one mRNA vaccine dose and offers a “green pass” (vaccine passport) to those with a positive serological result regardless of vaccination.19 In the European Union, people are eligible for an EU digital covid certificate after a single dose of an mRNA vaccine if they have had a positive test result within the past six months, allowing travel between 27 EU member states.20 In the UK, people with a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result can obtain the NHS covid pass up until 180 days after infection.21

Although it’s too soon to say whether these systems are working smoothly or mitigating spread, the US has no category for people who have been infected. The CDC still recommends a full vaccination dose for all, which is now being mirrored in mandates. A spokesperson told The BMJ that “the immune response from vaccination is more predictable” and that based on current evidence, antibody responses after infection “vary widely by individual,” though studies are ongoing to “learn how much protection antibodies from infection may provide and how long that protection lasts.”

In June, Peter Marks, director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, which regulates vaccines, went a step further and stated: “We do know that the immunity after vaccination is better than the immunity after natural infection.” In an email, an FDA spokesperson said Marks’s comment was based on a laboratory study of the binding breadth of Moderna vaccine induced antibodies.22The research did not measure any clinical outcomes. Marks added, referring to antibodies, that “generally the immunity after natural infection tends to wane after about 90 days.”23

“It appears from the literature that natural infection provides immunity, but that immunity is seemingly not as strong and may not be as long lasting as that provided by the vaccine,” Alfred Sommer, dean emeritus of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health tells The BMJ.

But not everyone agrees with this interpretation. “The data we have right now suggests that there probably isn’t a whole lot of difference” in terms of immunity to the spike protein, says Matthew Memoli, director of the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases Clinical Studies at the NIH, who spoke to The BMJ in a personal capacity.

Memoli highlights real world data such as the Cleveland Clinic study18 and points out that while “vaccines are focused on only that tiny portion of immunity that can be induced” by the spike, someone who has had covid-19 was exposed to the whole virus, “which would likely offer a broader based immunity” that would be more protective against variants. The laboratory study offered by the FDA22 “only has to do with very specific antibodies to a very specific region of the virus [the spike],” says Memoli. “Claiming this as data supporting that vaccines are better than natural immunity is shortsighted and demonstrates a lack of understanding of the complexity of immunity to respiratory viruses.”

Antibodies

Much of the debate pivots on the importance of sustained antibody protection. In April, Anthony Fauci told US radio host Maria Hinajosa that people who have had covid-19 (including Hinajosa) still need to be “boosted” by vaccination because “your antibodies will go sky high.”

“That’s still what we’re hearing from Dr Fauci—he’s a strong believer that higher antibody titres are going to be more protective against the variants,” says Jeffrey Klausner, a clinical professor of preventive medicine at the University of Southern California and former CDC medical officer, who has spoken out in favour of treating prior infection as equivalent to vaccination, with “the same societal status.”3 Klausner conducted a systematic review of 10 studies on reinfection and concluded that the “protective effect” of a previous infection “is high and similar to the protective effect of vaccination.”

In vaccine trials, antibodies are higher in participants who were seropositive at baseline than in those who were seronegative.24 However, Memoli questions the importance: “We don’t know that that means it’s better protection.”

Former CDC director Tom Frieden, a proponent of universal vaccination, echoes that uncertainty: “We don’t know that antibody level is what determines protection.”

Gandhi and others have been urging reporters away from antibodies as the defining metric of immunity. “It is accurate that your antibodies will go down” after natural infection, she says—that’s how the immune system works. If antibodies didn’t clear from our bloodstream after we recover from a respiratory infection, “our blood would be thick as molasses.”

“The real memory in our immune system resides in the [T and B] cells, not in the antibodies themselves,” says Patrick Whelan, a paediatric rheumatologist at University of California, Los Angeles. He points out that his sickest covid-19 patients in intensive care, including children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome, have “had loads of antibodies ... So the question is, why didn’t they protect them?”

Antonio Bertoletti, a professor of infectious disease at Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, has conducted research that indicates T cells may be more important than antibodies. Comparing the T cell response in people with symptomatic versus asymptomatic covid-19, Bertoletti’s team found them to be identical, suggesting that the severity of infection does not predict strength of resulting immunity and that people with asymptomatic infections “mount a highly functional virus specific cellular immune response.”25

Already complicated rollout

While some argue that the pandemic strategy should not be “one size fits all,” and that natural immunity should count, other public health experts say universal vaccination is a more quantifiable, predictable, reliable, and feasible way to protect the population.

Frieden told The BMJ that the question of leveraging natural immunity is a “reasonable discussion,” one he had raised informally with the CDC at start of rollout. “I thought from a rational standpoint, with limited vaccine available, why don’t you have the option” for people with previous infection to defer until there was more supply, he says. “I think that would have been a rational policy. It would have also made rollout, which was already too complicated, even more complicated.”

Most infections were never diagnosed, Frieden points out, and many people may have assumed they had been infected when they hadn’t. Add to that false positive results, he says. Had the CDC given different directives and vaccine schedules based on prior infection, it “wouldn’t have done much good and might have done some harm.”

Klausner, who is also a medical director of a US testing and vaccine distribution company, says he initiated conversations about offering a fingerprick antibody screen for people with suspected exposure before vaccination, so that doses could be used more judiciously. But “everyone concluded it was just too complicated.”

“It’s a lot easier to put a shot in their arm,” says Sommer. “To do a PCR test or to do an antibody test and then to process it and then to get the information to them and then to let them think about it—it’s a lot easier to just give them the damn vaccine.” In public health, “the primary objective is to protect as many people as you can,” he says. “It’s called collective insurance, and I think it’s irresponsible from a public health perspective to let people pick and choose what they want to do.”

But Klausner, Gandhi, and others raise the question of fairness for the millions of Americans who already have records of positive covid test results—the basis for “recovered” status in Europe—and equity for those at risk who are waiting to get their first dose (an argument being raised anew as US officials announce boosters while the virus spreads in countries lacking vaccine supply). For people who did not have a confirmed positive result but suspected previous infection, reliable antibody tests have been accessible “at least since April,” according to Klausner, though in May, the FDA announced that “antibody tests should not be used to evaluate a person’s level of immunity or protection from covid-19 at any time.”26

Unlike Europe, the US doesn’t have a national certificate or vaccination requirement, so defenders of natural immunity have simply advocated for more targeted recommendations and screening availability—and that mandates allow for exemptions. Logistics aside, a recognition of existing immunity would have fundamentally changed the target vaccination calculations and would also affect the calculations on boosters. “As we continued to put effort into vaccination and set targets, it became apparent to me that people were forgetting that herd immunity is formed by both natural immunity and vaccine immunity,” says Klausner.

Gandhi thinks logistics is only part of the story. “There’s a very clear message out there that ‘OK, well natural infection does cause immunity but it’s still better to get vaccinated,’ and that message is not based on data,” says Gandhi. “There’s something political going on around that.”

Politics of natural immunity

Early in the pandemic, the question of natural immunity was on the mind of Ezekiel Emanuel, a bioethicist at the University of Pennsylvania and senior fellow at the liberal think tank Center for American Progress, who later became a covid adviser to President Biden. He emailed Fauci before dawn on 4 March 2020. Within a few hours, Fauci wrote back: “you would assume that their [sic] would be substantial immunity post infection.”27

That was before natural immunity started to be promoted by Republic politicians. In May 2020, Kentucky senator and physician Rand Paul asserted that since he already had the virus, he didn’t need to wear a mask. He has been the most vocal since, arguing that his immunity exempted him from vaccination. Wisconsin senator Ron Johnson and Kentucky representative Thomas Massie have also spoken out. And then there was President Trump, who tweeted last October that his recovery from covid-19 rendered him “immune” (which Twitter labelled “misleading and potentially harmful information”).

Another polarising factor may have been the Great Barrington declaration of October 2020, which argued for a less restrictive pandemic strategy that would help build herd immunity through natural infections in people at minimal risk.28 The John Snow memorandum, written in response (with signatories including Rochelle Walensky, who went on to head the CDC), stated “there is no evidence for lasting protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 following natural infection.”29 That statement has a footnote to a study of people who had recovered from covid-19, showing that blood antibody levels wane over time.

More recently, the CDC made headlines with an observational study aiming to characterise the protection a vaccine might give to people with past infections. Comparing 246 Kentuckians who had subsequent reinfections with 492 controls who had not, the CDC concluded that those who were unvaccinated had more than twice the odds of reinfection.30 The study notes the limitation that the vaccinated are “possibly less likely to get tested. Therefore, the association of reinfection and lack of vaccination might be overestimated.” In announcing the study, Walensky stated: “If you have had covid-19 before, please still get vaccinated.”31

“If you listen to the language of our public health officials, they talk about the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Makary tells The BMJ. “If we want to be scientific, we should talk about the immune and the non-immune.” There’s a significant portion of the population, Makary says, who are saying, “‘Hey, wait, I’ve had [covid].’ And they’ve been blown off and dismissed.”

Different risk-benefit analysis?

For Frieden, vaccinating people who have already had covid-19 is, ultimately, the most responsible policy right now. “There’s no doubt that natural infection does provide significant immunity for many people, but we’re operating in an environment of imperfect information, and in that environment the precautionary principle applies—better safe than sorry.”

“In public health you are always dealing with some level of unknown,” says Sommer. “But the bottom line is you want to save lives, and you have to do what the present evidence, as weak as it is, suggests is the strongest defence with the least amount of harm.”

But others are less certain.

“If natural immunity is strongly protective, as the evidence to date suggests it is, then vaccinating people who have had covid-19 would seem to offer nothing or very little to benefit, logically leaving only harms—both the harms we already know about as well as those still unknown,” says Christine Stabell Benn, vaccinologist and professor in global health at the University of Southern Denmark. The CDC has acknowledged the small but serious risks of heart inflammation and blood clots after vaccination, especially in younger people. The real risk in vaccinating people who have had covid-19 “is of doing more harm than good,” she says.

A large study in the UK32 and another that surveyed people internationally33 found that people with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection experienced greater rates of side effects after vaccination. Among 2000 people who completed an online survey after vaccination, those with a history of covid-19 were 56% more likely to experience a severe side effect that required hospital care.33

Patrick Whelan, of UCLA, says the “sky high” antibodies after vaccination in people who were previously infected may have contributed to these systemic side effects. “Most people who were previously ill with covid-19 have antibodies against the spike protein. If they are subsequently vaccinated, those antibodies and the products of the vaccine can form what are called immune complexes,” he explains, which may get deposited in places like the joints, meninges, and even kidneys, creating symptoms.

Other studies suggest that a two dose regimen may be counterproductive.34 One found that in people with past infections, the first dose boosted T cells and antibodies but that the second dose seemed to indicate an “exhaustion,” and in some cases even a deletion, of T cells.34 “I’m not here to say that it’s harmful,” says Bertoletti, who coauthored the study, “but at the moment all the data are telling us that it doesn’t make any sense to give a second vaccination dose in the very short term to someone who was already infected. Their immune response is already very high.”

Despite the extensive global spread of the virus, the previously infected population “hasn’t been studied well as a group,” says Whelan. Memoli says he is also unaware of any studies examining the specific risks of vaccination for that group. Still, the US public health messaging has been firm and consistent: everyone should get a full vaccine dose.

“When the vaccine was rolled out the goal should have been to focus on people at risk, and that should still be the focus,” says Memoli. Such risk stratification may have complicated logistics, but it would also require more nuanced messaging. “A lot of public health people have this notion that if the public is told that there’s even the slightest bit of uncertainty about a vaccine, then they won’t get it,” he says. For Memoli, this reflects a bygone paternalism. “I always think it’s much better to be very clear and honest about what we do and don’t know, what the risks and benefits are, and allow people to make decisions for themselves.”

Footnotes

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ's website terms and conditions for the duration of the covid-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.https://bmj.com/coronavirus/usage

References

↵

CDC. Estimated disease burden of COVID-19. Feb-Sep 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20210115184811/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/burden.html

↵

We’ll have herd immunity by April. Wall Street Journal 2021 https://www.wsj.com/articles/well-have-herd-immunity-by-april-11613669731

↵

Klausner J. Op-Ed: Quit ignoring natural covid. Medpage Today 2021 May 28. Immunity. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/92836

↵

Natural immunity to covid-19: taking politics out of science. Monica Gandhi, MD, talks to Marty Makary, MD, about the data beyond the debate. Medpage Today 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/90894

↵

Had covid? You may only need one dose of vaccine, study says. New York Times 2021 Feb 8. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/01/health/have-you-had-covid-19-coronavirus.html

↵

CDC. Frequently asked questions about covid-19 vaccination. 25 Jan 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210131060730/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html

↵

KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: June 2021.https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-june-2021/

↵

Block J. US college covid-19 vaccine mandates don’t consider immunity or pregnancy, and may run foul of the law. BMJ2021;373:n1397. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1397 pmid:34078619

FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵

Dan JM,

Mateus J,

Kato Y,

et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science2021;371:eabf4063. doi:10.1126/science.abf4063 pmid:33408181

Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵

Redd AD, Nardin A, Kared H, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses in covid-19 convalescent individuals target conserved epitopes from multiple prominent SARS-CoV-2 circulating variants. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2021;8: ofab143.

↵

Tarke A,

Sidney J,

Methot N,

et al. Negligible impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell reactivity in COVID-19 exposed donors and vaccines.bioRxiv 2021.02.27.433180. [Preprint.] doi:10.1101/2021.02.27.433180

Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵

Ghandi M. Twitter post 8 May 2021. [REMOVED IF= FIELD]https://twitter.com/MonicaGandhi9/status/1391139927442690048

↵

NIH. Lasting immunity found after recovery from COVID-19. 2021. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/lasting-immunity-found-after-recovery-covid-19#main-content

↵

O Murchu E,

Byrne P,

Carty PG,

et al. Quantifying the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection over time. Rev Med Virol2021:e2260.pmid:34043841

PubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

Bertollini R,

Chemaitelly H,

Yassine HM,

Al-Thani MH,

Al-Khal A,

Abu-Raddad LJ. Associations of vaccination and of prior infection with positive PCR test results for SARS-CoV-2 in airline passengers arriving in Qatar. JAMA2021;326:185-8.doi:10.1001/jama.2021.9970 pmid:34106201

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

Hall VJ,

Foulkes S,

Charlett A,

et al.,

SIREN Study Group. SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of antibody-positive compared with antibody-negative health-care workers in England: a large, multicentre, prospective cohort study (SIREN). Lancet2021;397:1459-69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00675-9 pmid:33844963

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

Goldberg Y,

Mandel M,

Woodbridge Y, et al. Protection of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection is similar to that of BNT162b2 vaccine protection: A three-month nationwide experience from Israel. [Preprint.] medRxiv2021.04.20.21255670.doi:10.1101/2021.04.20.21255670

Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵

Shrestha NK,

Burke PC,

Niowacki AS,

Terpeluk P,

Gordon SM. Necessity of COVID-19 vaccination in previously infected individuals.[Preprint.] medRxiv2021.06.01.21258176; doi:10.1101/2021.06.01.21258176

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

↵

What is a green pass? https://corona.health.gov.il/en/directives/green-pass-info/

↵

Questions and answers —EU digital covid certificate. Jun 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_21_2781

↵

UK Department of Health and Social Care. Who can get an NHS COVID Pass in England. 26 Aug 2021. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/nhs-covid-pass#who-can-get-an-nhs-covid-pass-in-england

↵

Greaney AJ,

Loes AN,

Gentles LE,

et al. Antibodies elicited by mRNA-1273 vaccination bind more broadly to the receptor binding domain than do those from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Transl Med2021;13:eabi9915.doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abi9915 pmid:34103407

Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

↵

Janet Woodcock and Peter Marks discuss the suggested increased risks of myocarditis and pericarditis following covid-19 vaccination. 6 Jul 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_j8ziaOpl7o&t=1724s

↵

FDA. Pfizer-BioNTech covid-19 vaccine EUA amendment review memorandum. Table 9. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/148542/download#page=19

↵

Le Bert N,

Clapham HE,

Tan AT,

et al. Highly functional virus-specific cellular immune response in asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Exp Med2021;218:e20202617. . doi:10.1084/jem.20202617 pmid:33646265

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

FDA. Antibody testing is not currently recommended to assess immunity after covid-19 vaccination: FDA safety communication, 19 May 2021. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/antibody-testing-not-currently-recommended-assess-immunity-after-covid-19-vaccination-fda-safety

↵

Anthony Fauci emails. 4 Mar 2021. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/20793561/leopold-nih-foia-anthony-fauci-emails.pdf

↵

Great Barrington declaration, https://gbdeclaration.org/

↵

John Snow memorandum. https://www.johnsnowmemo.com/john-snow-memo.html

↵

Cavanaugh AM,

Spicer KB,

Thoroughman D,

Glick C,

Winter K. Reduced risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19 vaccination—Kentucky, May-June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2021;70:1081-3.doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7032e1 pmid:34383732

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

CDC. New CDC Study: Vaccination offers higher protection than previous covid-19 infection. Press release, 6 Aug 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0806-vaccination-protection.html

↵

Menni C,

Klaser K,

May A,

et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis2021;21:939-49. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3 pmid:33930320

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

Mathioudakis AG,

Ghrew M,

Ustianowski A,

et al. Self-reported real-world safety and reactogenicity of covid-19 vaccines: a vaccine recipient survey. Life (Basel)2021;11:249. doi:10.3390/life11030249 pmid:33803014

CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

↵

Camara C,

Lozano-Ojalvo D,

Lopez-Grandados E. Differential effects of the second SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine dose on T cell immunity in naïve and COVID-19 recovered individuals. Cell Rep 2021;36:109570. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109570

CrossRefGoogle ScholarView Abstract

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)